BILL BRUFORD – Intervista al batterista e compositore inglese

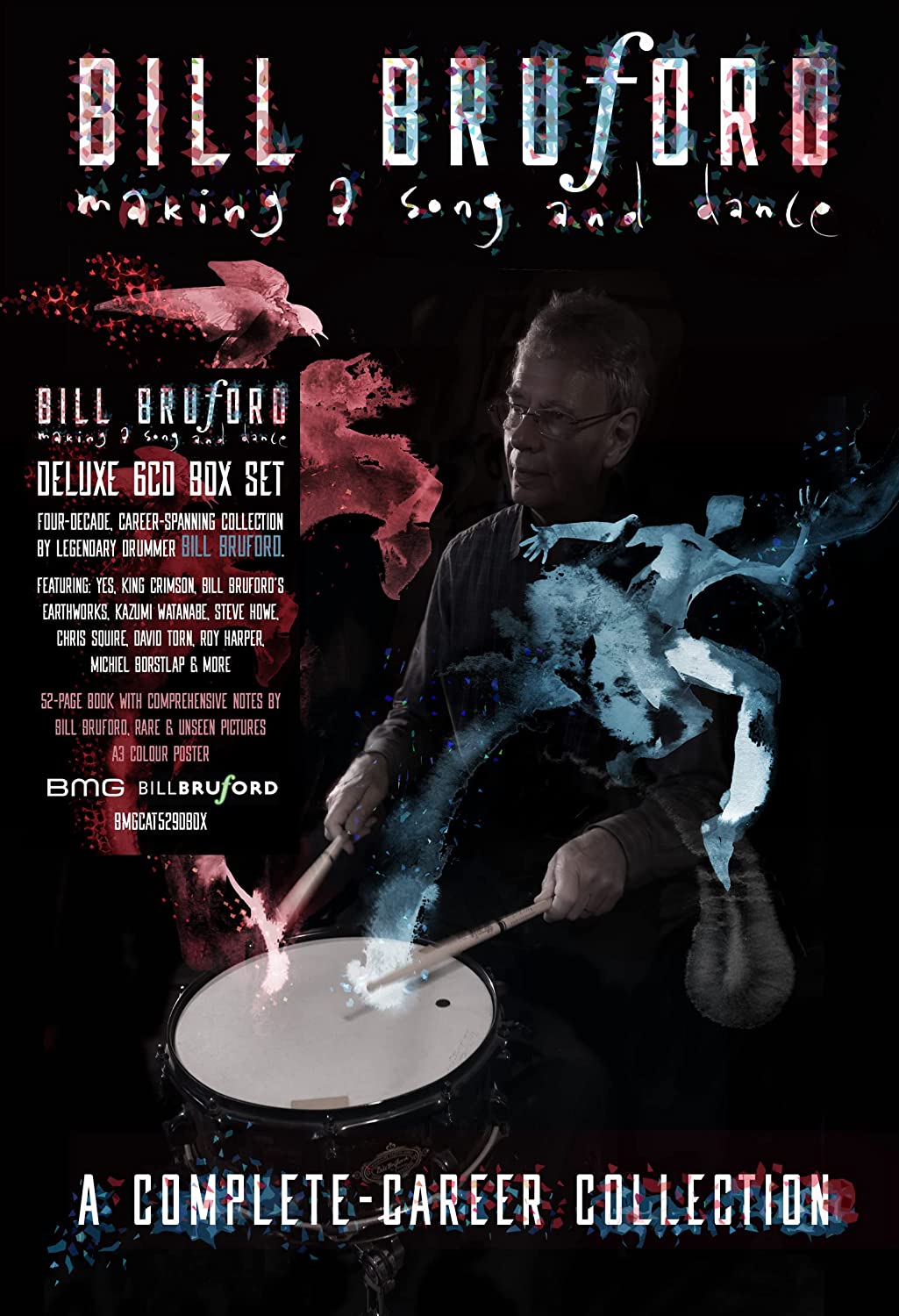

La storia del progressive rock, infinite intuizioni musicali dal jazz rock alla sperimentazione e tentazioni elettroniche e poi batterista del periodo migliore degli Yes, ma anche dei King Crimson e collaborazioni con Genesis, Gong, UK e National Health e la parentesi jazz con i suoi Earthworks e tantissime altre collaborazioni. Tutto questo e tanto altro è Bill Bruford che si è concesso alle nostre pagina in questa intervista dove ci racconta del passato, del presente e del futuro, tutto racchiuso anche nel suo box di 6 cd da poco uscito “Making A Song And Dance: The Complete Career Collection”.

Ciao Bill e benvenuto su Tuttorock.com. 50 anni di storia in un cofanetto di 6 cd, come è nata l’idea?

Insolitamente, l’idea mi è venuta da una casa discografica. La BMG Records ha suggerito che avrebbero voluto farlo. Hanno esperienza nei cataloghi precedenti di artisti “heritage” o “legacy”. Avevo appena realizzato due cofanetti nei tre anni precedenti, quindi non ci stavo pensando, ma l’accesso di BMG al mio catalogo completo ha reso il tutto una proposta molto allettante.

Come hai scelto le canzoni da inserire nel box?

C’erano una serie di parametri, ma c’era molta musica tra cui scegliere. Sei CD ti danno circa 70 tracce. Non erano organizzati cronologicamente, ma piuttosto per temi di come si esibiscono i batteristi. Nel mio caso, mi sono esibito in collaborazione con altri (apparentemente band come Yes e King Crimson non avevano leader); oppure mi sono esibito come leader (Bruford, Earthworks); o per un leader come ospite speciale (Al Di Meoloa, Roy Harper), o senza leader, in musica improvvisata (Bruford-Borstlap, Moraz-Bruford). Questi quattro temi sono rappresentati rispettivamente sui dischi 1 e 2, sui dischi 3 e 4, sul disco 5 e sul disco 6.

King Crimson, sì, ma anche UK, Genesis e National Health e poi la parentesi jazz e fusion. È tutto il mondo di Bill Bruford? Cos’altro c’è nella tua arte anche nel futuro?

Mi sono ritirato dallo spettacolo pubblico nel 2009 dopo 41 anni. Ciò mi ha permesso di fare un passo indietro e considerare l’habitus del batterista nel senso più ampio: è la psicologia culturale, la sua posizione nel firmamento strumentale come strumento musicale non intonato, le condizioni di impiego dei suoi praticanti, la quasi impossibilità di guadagnarsi da vivere esclusivamente sullo strumento, le relative nevrosi e problemi, e così via. Penso di voler contribuire ora meno con una batteria e più con la parola scritta, come questa intervista.

Aprendo il libro dei tuoi ricordi, alcuni sono in questa scatola, quali sono i momenti che ricordi con più entusiasmo e quali quelli che ti emozionano di meno?

Ricordo l’intera faccenda, le verruche e tutto il resto, le parti positive e quelle negative, con molto affetto per i miei colleghi musicisti, la maggior parte dei quali cercava sempre di dare il meglio di sé. C’è un sacco di piacere da provare nel sedersi indietro. Era sempre emozionante. Sono uno dei pochissimi musicisti che possono onestamente dire di aver suonato la musica che volevo, quando, dove e con chi volevo suonarla. Ho avuto la fortuna e il privilegio di poterlo fare. Molti musicisti non sono molto interessati alla musica che devono suonare quella sera. Ricordo di essere stato completamente esasperato con Robert Fripp dei King Crimson – esasperato quasi quanto lo era con me – in una sala prove a Nashville, nel Tennessee, intorno al 1996. Sapevo per certo che non mi sarei più esibito con la band. Qualcosa di straordinario era finito e le sue implicazioni mi rimbombavano in testa da allora. Ma ho la pelle dura e resiliente. Anche mentre mi riprendevo da quella prova, potevo sentire il suono di una porta che si chiudeva ma un’altra si apriva.

Per un po’ hai dato importanza alla batteria elettronica, perché?

Perché era interessante, ed è mio compito come artista notare cose interessanti, collegarle a cose ricordate e creare qualcosa di nuovo. Erano difficili da gestire, elettronicamente sospette e appesantite da un’assurda campagna promozionale che diceva ai batteristi “Questo è il futuro…non avrete più bisogno della vostra batteria acustica” che era palesemente stupida. Tuttavia, ho potuto sentire un possibile utilizzo per loro nei King Crimson (Waiting Man, No Warning, gran parte di “Three of a Perfect Pair”) e più tardi, quando lo strumento si è sviluppato molto, con Earthworks. In Earthworks, sono stato in grado di suonare accordi e armonie, a volte combinati con le percussioni (Stromboli Kicks, Candles Still Flicker in Romania’s Dark, Pilgrim’s Way). Oggi i giovani batteristi sono molto più sofisticati di quanto potessi essere io. Hanno una fluidità nei loro kit ibridi, combinando elettronica e acustica in modi sottili e sorprendenti.

Oggi la musica e il suo modo di farla è molto diverso da quello che hai iniziato a fare anni fa. Come vedi la scena musicale oggi, che sia progressive o rock o jazz? Quali sono i tuoi ascolti oggi e se ci sono band giovani che ti piacciono.

Sono un autore accademico ormai da dieci anni e non ascolto molte giovani band a meno che mio figlio non mi ordini di farlo. I midi neri sono molto nitidi; così anche Half Moon Run. E ci sono giovani batteristi eccezionali in giro: Louis Cole, Karriem Riggins, Mark Guiliana, Eric Harland, Dan Weiss. Ma è una scena difficile. Contrariamente a quanto la Silicon Valley vorrebbe far credere, ci sono più persone nella “economia dell’attenzione” che cercano un paio di orecchie per ascoltare che mai. Quindi la domanda centrale diventa, come mantenere vivi (il tuo corpo e) la tua anima e guadagnarti da vivere come artista? Ma i generi “rock” e “jazz”, con i loro numerosi sottogeneri, stanno iniziando, in un mondo dopo l’hip-hop, a puzzare di decadenza.

Che consiglio daresti a un giovane batterista per diventare un nuovo Bill Bruford?

Dimentica l’idea di essere un nuovo Bill Bruford. Ne abbiamo avuto uno. Vogliamo il nuovo te. Un buon consiglio è quello di ascoltare più ampiamente. Ascolta l’inizio del kit drumming nei primi anni del 1900 e avanti fino ai giorni nostri. Chiediti “come siamo arrivati da lì a qui, e cosa suoneremo tra cinque o dieci anni?” Ascolta molta musica senza drum kit. Funziona molto bene, quindi cosa stai facendo di così speciale che qualcuno deve pagarti per venire a farlo? Non preoccuparti di “formare un gruppo” – troppo costoso, un incubo logistico – trova invece un unico partner musicale, su qualsiasi strumento o nessuno, che la pensi allo stesso modo della musica come te. E poi iniziare a generare materiale di qualsiasi descrizione insieme, e non giudicare la qualità di ciò che produci. Altri lo faranno in abbondanza per te in due corsi! Impara ad ascoltare e poi ascolta.

Dai una chiave di lettura per assimilare meglio i 6 cd contenuti nel cofanetto! Inizia dal primo e in sequenza o come?

In precedenza ho risposto alla domanda su come è disposta la musica nel box. È organizzato tematicamente, non cronologicamente. Suggerisco se vuoi ascoltare collaborazioni con altre persone in band come Yes o UK, vai ai CD 1 e 2. Se vuoi sentire come ho operato quando sotto la direzione di altri come ospite speciale, eseguendo la loro musica, prova CD 5. Se vuoi sentire come reagisco con qualsiasi materiale preparato, in un contesto di improvvisazione, prova qualsiasi cosa sul CD 6. I CD 3 e 4 presentano registrazioni di uno spaccato del mio lavoro come leader con i gruppi Bruford, Earthworks o Bruford-Levin.

Dopo questo box, quali saranno i tuoi progetti futuri?

Ho fatto molto di recente. Nel 2010 ho pubblicato un’autobiografia. Poi sono tornato all’università per ottenere un dottorato in musicologia (2016) presso l’Università del Surrey. Il mio primo cofanetto “Seems Like a Lifetime Ago” della mia band “Bruford” è stato pubblicato nel 2017. Il mio volume più recente “Uncharted: Creativity and the Expert Drummer” è stato pubblicato dalla University of Michigan Press (2018). Un secondo cofanetto – Earthworks Complete – è stato rilasciato nel 2019, e ora stiamo discutendo del terzo cofanetto in cinque anni, Making a Song and Dance’! Ora posso semplicemente sedermi a lato del campo e guardare con stupore come si sviluppano la musica e la batteria.

Grazie Bill, chiudi l’intervista come vuoi, per i nostri lettori e per i tuoi tanti fan italiani. Un messaggio in un periodo difficile tra pandemia e guerra.

Con i ringraziamenti a tutti i miei amici italiani che sono stati così gentili da prestarmi le loro orecchie per decenni, spero sinceramente che vi piaccia quello che c’è nel box. Vorrei offrire le parole del romanziere Henry Miller:

“Sto pensando che in quell’età a venire non sarò trascurato. Allora la mia storia diventerà importante e la cicatrice che lascerò sulla faccia del mondo avrà un significato”.

(Henry Miller: ‘Black Spring’ p. 23)

FABIO LOFFREDO

** ENGLISH VERSION **

Hi Bill and welcome to Tuttorock.com. 50 years of history in a 6 CD box, how did the idea come about?

Unusually, the idea came to me from a record company. BMG Records suggested they’d like to do this. They have experience in ‘heritage’ or ‘legacy’ artists’ back catalogues. I’d just done two box sets in the previous three years, so wasn’t thinking about it, but BMG’s access to my full catalogue made the whole thing a very tempting proposition.

How did you choose the songs to be included in the box?

There were a number of parameters, but there was a lot of music to choose from. Six CDs gives you about 70 tracks. They were arranged not chronologically, but rather by themes of how drummers perform. In my case, I performed with others collaboratively (bands like Yes and King Crimson ostensibly didn’t have leaders); or I performed as a leader (Bruford, Earthworks); or for a leader as a special guest (Al Di Meoloa, Roy Harper), or without a leader, in improvised music (Bruford-Borstlap, Moraz-Bruford). These four themes are represented on discs 1 & 2, discs 3 & 4, disc 5, and disc 6 respectively.

King Crimson, Yes, but also UK Genesis and National Health and then the jazz and fusion parenthesis. Is it all of Bill Bruford’s world? What else is there in your art also in the future?

I retired from public performance in 2009 after 41 years. That allowed me to step back and consider the habitus of the drummer in the broadest sense: it’s cultural psychology, it’s position in the instrumental firmament as an unpitched musical instrument, the conditions of employment of its practitioners, the near impossibility of making a living solely on the instrument, the attendant neuroses and problems, and so on. I think I want to contribute now less with a drum kit and more with the written word, like this interview.

Opening the book of your memories, some are in this box, which are the moments that you remember with the most enthusiasm and which ones that excite you the least?

I remember the whole thing, warts and all, the good bits and the bad bits, with a great deal of affection for my musical colleagues, most of whom were always trying to give their best. There is a lot of pleasure to be had in the lsitening back. It was always exciting. I’m one of very few musicians who can honestly say that I played the music I wanted, when, where and with whom I wanted to play it. I was fortunate and privileged to be able to do that. A lot of musicians are not very interested in the music they have to play that night. I remember being completely exasperated with Robert Fripp of King Crimson – almost as exasperated as he was with me – in a rehearsal room in Nashville, Tennessee in about 1996. I knew for sure I wouldn’t be performing with the band again. Something extraordinary had ended and its implications have rattled around in my head ever-since. But I am thick-skinned and resilient. Even as I was picking myself up from that rehearsal, I could hear the sound of one door closing but another one opening.

For a while you have given importance to electronic drums, why?

Because they were interesting, and it’s my job as an artist to notice interesting things, connect them to things remembered and make something new. They were difficult to handle, electronically suspect, and saddled with an absurd promotional campaign that said to drummers’ “This is the future…you’ll never need your acoustic drums any more” which was patently stupid. Nevertheless, I could hear a possible use for them in King Crimson (Waiting Man, No Warning, much of ‘Three of a Perfect Pair’) and later on when the instrument had developed a lot, with Earthworks. In Earthworks, I was able to play chords and harmony, sometimes combined with percussion (Stromboli Kicks, Candles Still Flicker in Romania’s Dark, Pilgrim’s Way). Today, young players are much more sophisticated than I was able to be. They have a fluidity on their hybrid kits, combining electronics and acoustics in subtle and surprising ways.

Today music and its way of making it is very different from what you started doing years ago. How do you see the music scene today, be it progressive or rock or jazz? What are your ratings today and if there are any young bands you like.

I have been an academic author now for ten years and don’t listen to many young bands unless my son orders me to do so. Black Midi are very sharp; so too are Half Moon Run. And there are exceptional young drummers around: Louis Cole, Karriem Riggins, Mark Guiliana, Eric Harland, Dan Weiss. But it’s a difficult scene. Contrary to what Silicon Valley would have you believe, there are more people in the ‘attention economy’ searching for a pair of ears to hear than ever before. So the central question becomes, how to keep your (body and) soul alive and still make a living as an artist? But the genres of ‘rock’ and ‘jazz’, with their many sub-genres, are, in a world after hip-hop, beginning to smell of decay.

What advice would you give to a young drummer to become a new Bill Bruford?

Forget the idea of being a new Bill Bruford. We’ve had one of them. We want the new you. One good piece of advice is to listen more widely. Listen back to the beginning of kit drumming in the early 1900s and forward to the modern day. Ask yourself “how did we get from there to here, and what are we going to be playing in five or ten years time?” Listen to lots of music without drumkit at all. It works extremely well, so what are you doing that is so special that someone needs to pay you to come and do it? Don’t bother to ‘form a group’ – too expensive, a logistical nightmare – instead, find a single musical partner, on any instrument or none, who thinks the same way about music as you do. And then starting generating material of any description together, and don’t judge the quality of what you produce. Others will do plenty of that for you in due course! Learn how to listen, and then listen.

Give a reading key to better assimilate the 6 CDs in the box! Start from the first and in sequence or how?

Earlier I answered the question of how the music in the box is arranged. It is arranged thematically, not chronologically. I suggest if you want to hear collaborations with other people in bands like Yes or UK, go to CDs 1 & 2. If you want to hear how I operated when under the direction of others as a special guest, performing their music, try CD 5. If you’d like to hear how I react withput any prepared material at all, in an improvisational context, try anything on CD 6. CDs 3 & 4 present recordings of a cross-section of my work as a leader with the groups Bruford, Earthworks or Bruford-Levin.

After this box, what will your future projects be?

I have done a lot recently. In 2010, I published an autobiography. Then I returned to University to gain a doctorate in musicology (2016) from the University of Surrey. My first box set ‘Seems Like a Lifetime Ago’ by my band ‘Bruford’ was released in 2017. My most recent volume ‘Uncharted: Creativity and the Expert Drummer’ was published by the University of Michigan Press (2018). A second box set – Earthworks Complete – was released 2019, and now we are discussing the third box set in five years, Making a Song and Dance’! Now I can just sit on the side of the pitch and watch with astonishment how music and drumming develops.

Thank you Bill, close the interview as you wish, for our readers and for your many Italian fans. A message in a difficult period between pandemic and war.

With thanks to all my Italian friends who have been kind enough to lend me their ears over decades, I sincerely hope you enjoy what’s in the box. I’d like to offer the words of novelist Henry Miller:

“I am thinking that in that age to come I shall not be overlooked. Then my history will become important and the scar which I leave upon the face of the world will have significance”.

(Henry Miller: ‘Black Spring’ p. 23)

FABIO LOFFREDO

Appassionato di musica sin da piccolo, ho cercato di esplorare vari generi musicali, ma è il metal, l'hard rock ed il rock progressivo, i generi musicali che più mi appassionano da molti anni. Chitarrista mancato, l'ho appesa al chiodo molto tempo fa. Ho mosso i primi passi nello scrivere di musica ad inizio anni 90, scrivendo per riviste come Flash (3 anni) e Metal Shock (ben 15 anni), qualche apparizione su MusikBox e poi il web, siti come Extramusic, Paperlate, Sdangher, Brutal Crush e Artists & Bands. I capelli mi si sono imbiancati, ma la passione per la musica è rimasta per me inalterata nel tempo, anzi molti mi dicono che non ho più speranze!!!!